From mpox to bird flu and beyond, multiple outbreaks of infectious diseases flared up around the world this year.

Dengue cases increased

It was a record year for dengue fever, a mosquito-borne disease. America has accumulated about 12.7 million cases since the beginning of December. This is about 90 percent of the approximately 14 million cases recorded worldwide. Cases in the Americas alone are also more than double the previous global record of 5.3 million cases reported by the WHO last year alone.

Climate change, El Niño and urbanization may have played a role in the massive outbreak, according to the WHO.

Rising temperatures may have increased dengue transmission by about 18 percent in the Americas and Asia compared to what it would have been in a world without warming, scientists reported in an article posted this year on medRxiv.org. Depending on the high level of global average temperature by 2050, transmission could become on average 40 to 57 percent higher than expected without climate change.

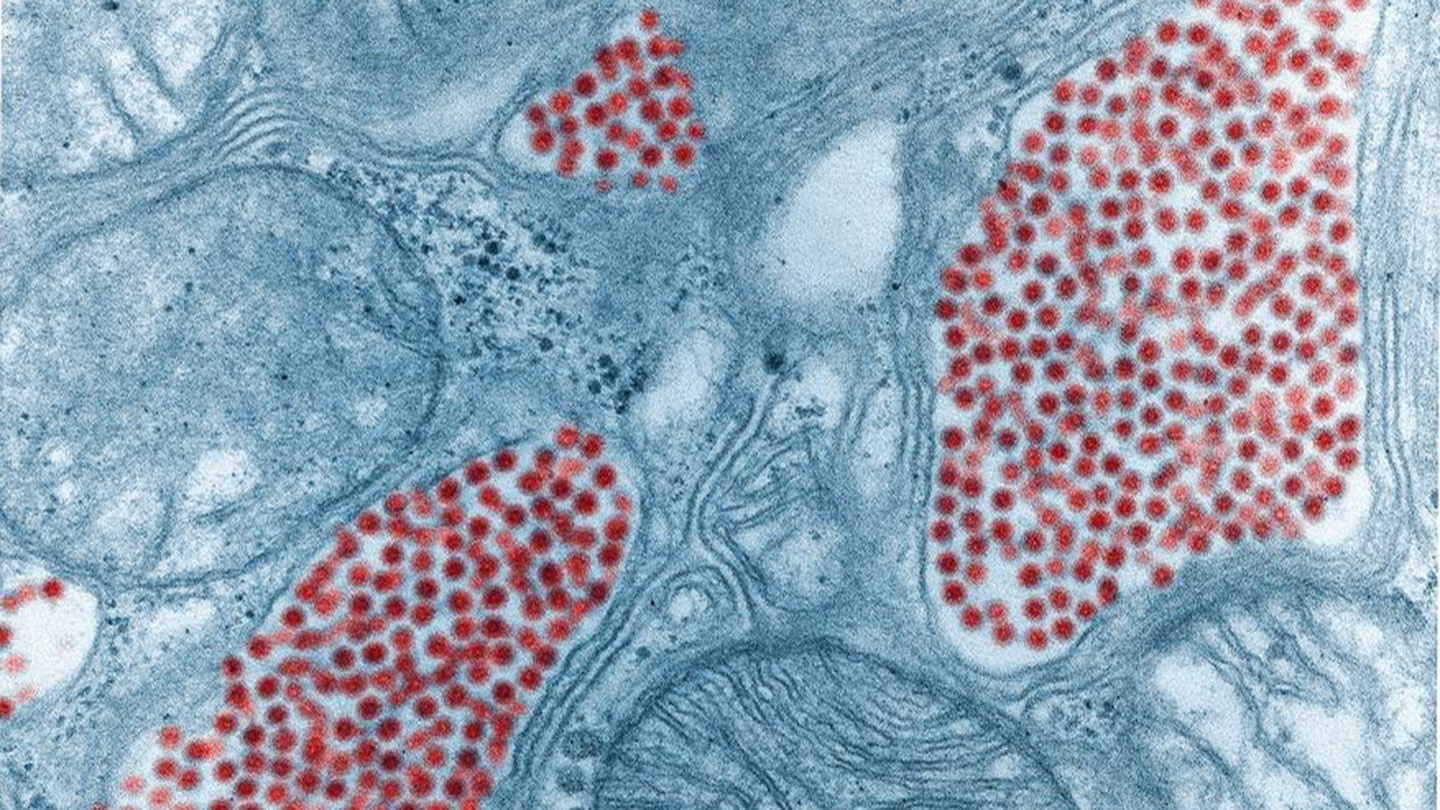

Mpox caused a global emergency

An increase in mpox cases across Central Africa reached a tipping point that prompted the World Health Organization to declare the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern in August (SN: 9/7/24 & 9/21/24, p.6).

Mpox, which can cause fever, muscle aches and a characteristic rash with painful pus-filled lesions, has long been a problem in parts of Africa. The Democratic Republic of Congo, where the first case was reported in 1970, is the center of the current outbreak. This year, the virus that causes mpox spread to previously unaffected countries, including Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda.

Since early December, there have been nearly 60,000 confirmed and suspected cases in 20 countries and 60 deaths in 2024. Children have been hit particularly hard.

Since the end of August, more than 170,000 doses of vaccine have been distributed in Nigeria, Congo and Rwanda. On November 19, the United Nations authorized the first mpox vaccine for children age 1 and older.

The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 10 million doses of vaccine are needed to control the outbreaks (SN: 19.9.24).

Bird flu made the jump to cows

The H5N1 outbreak that began spreading globally in 2021 continued to infect a host of wild birds, poultry and mammals this year (SN: 24.2.24, p. 14). And in late March, the virus jumped to an unexpected new animal: dairy cows.

The ongoing outbreak in US dairy cows has affected more than 700 herds in 16 states, with infections causing symptoms such as reduced milk production and lack of appetite. The virus infects the cow’s mammary glands, and studies suggest that contaminated milking equipment helps spread H5N1 from cow to cow (SN: 24.8.24, p. 9). High temperatures kill the virus, so pasteurized milk and cooked beef are safe to eat.

Since early December, 58 farm workers have tested positive for the virus after exposure to infected cattle. In August, a person in Missouri contracted the virus despite not having contact with cows or poultry. Another person living in the same household showed signs of a past infection, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in October. The finding suggests that the virus can sometimes, but rarely, spread from person to person through very close contact. Researchers are watching closely to see if new mutations arise that could help the virus spread easily between people.

Polio reared its head in Gaza

In September, WHO launched a mass polio vaccination campaign across Gaza after sewage samples tested positive for poliovirus and an infected 10-month-old boy developed paralysis in his left leg. Because paralysis from poliomyelitis is rare, a single case suggests hundreds of other infections. Israel’s military offensive against Hamas has destroyed much of Gaza’s health care and water treatment infrastructure, which likely helped the virus spread. Overall, 556,774 children were fully vaccinated, a coverage rate of 94 percent, WHO reported in November. Intense shelling and mass displacement in northern Gaza cut off access to many areas, leaving up to 10,000 children there not fully vaccinated.

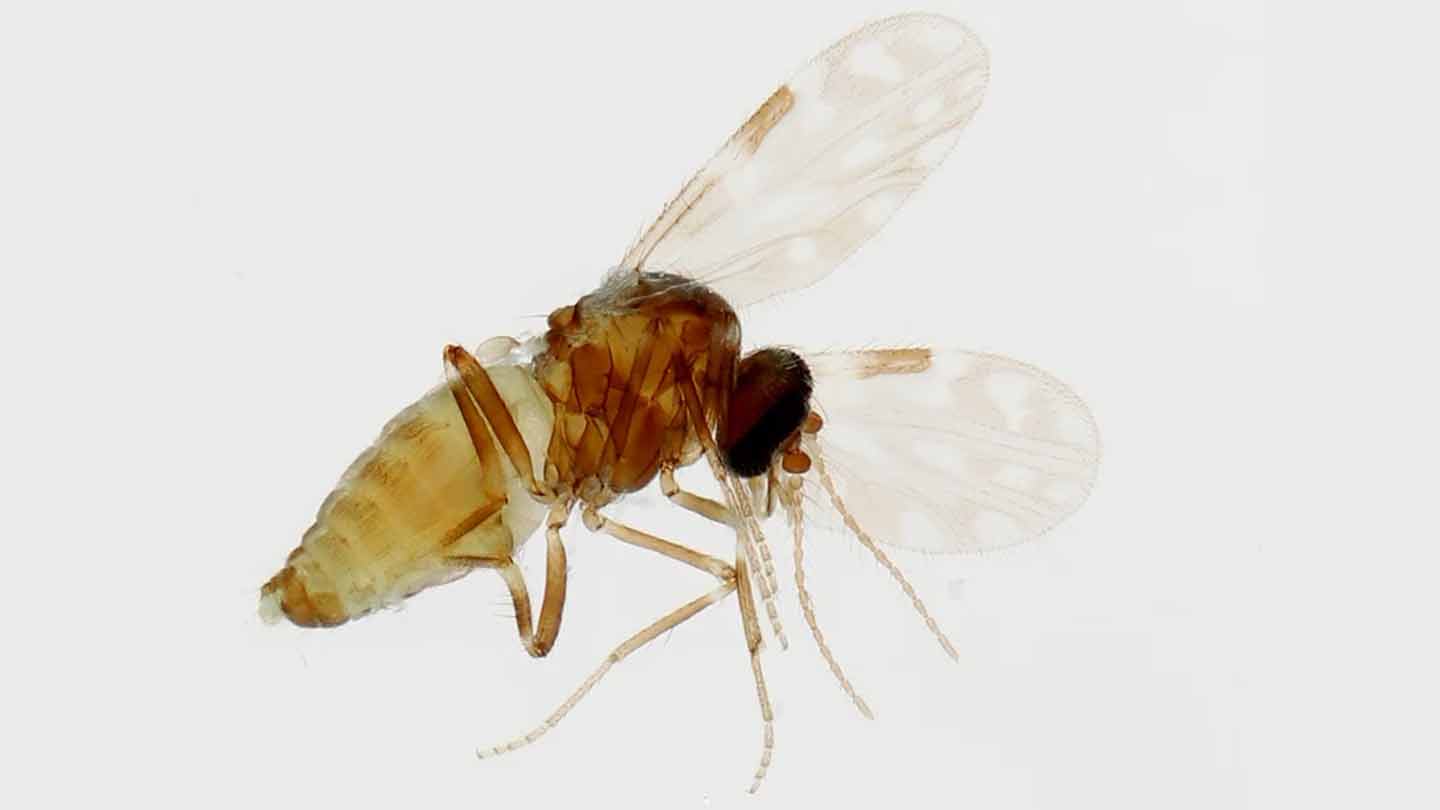

Oropouche fever became deadly

The Pan American Health Organization issued a health alert in August following an increase in confirmed cases of Oropouche fever. The virus that causes the disease – which is spread through insect bites and usually causes flu-like symptoms – hit new parts of South America and the Caribbean. Guyana, the Dominican Republic and Cuba all reported their first cases, as did several Brazilian states. It also became deadly for the first time, causing two deaths and one stillbirth in Brazil this summer (SN: 30.11.24, p. 15).

Triple E hit the East Coast

Health officials reported 16 cases of eastern equine encephalitis, or Triple E, in eight states along the US East Coast. This mosquito-borne viral infection occurs annually in the eastern and Gulf Coast states. The virus normally circulates in waterfowl and occasionally jumps to horses and humans. Most human cases go undetected because most people do not develop symptoms. Those who do may experience fever, body aches and joint pain. But in about 5 percent of cases, the virus invades the central nervous system, causing headaches, seizures, or behavioral changes. About a third of people with serious illnesses die. All cases reported in 2024 were neuroinvasive and three people died.

#viruses #defined #year

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org